Finally, the following broader issues were discussed

- Participants from Northern Ireland, Italy and Poland discussed concerns that online restorative work should be seen primarily as a unique response to current necessity. We should develop our skills and think differently because it is needed in the context of the crisis, but online work should not be normalised or take precedence following the crisis simply because it is cheaper. We need to make the argument in favour of being in the room together, where possible, for many reasons. Firstly, working online means that we lose, at least partially, the eye contact and body language that are crucial in communication. Secondly, while we may learn useful lessons from the literature on online and telephone counselling, this research notes that it is very difficult for professionals to avoid being more directing in their work when they are not in the same room as clients, while people simply do not interact as freely, easily or securely online. Indeed, online mediation might require a specific needs assessment because many persons are uncomfortable interacting in this way. Ultimately, after the crisis is over, it is important that we treat online approaches like shuttle mediation, that is, as an option when people cannot travel or otherwise cannot sit together. In the meantime, we should explore online platforms for e-mediation that exist in Europe, and that are used in the fields of corporate mediation and family mediation.

- The field of restorative justice is not in the business of profiting from harm and conflict. We must avoid the incidence or perception of offering the low quality and exploitative online services that some participants had seen taking place within mediation more broadly.

- Ultimately, there is a need for our services and we cannot stop because of the crisis. Restorative practitioners are servant to the parties, who are free, once fully informed of all the challenges and limitations, to decide that online approaches work for them or not. That being said, it is incumbent on us to use our professional judgement to distinguish between more or less urgent conflicts, and conflicts that are more or less conducive to online responses.

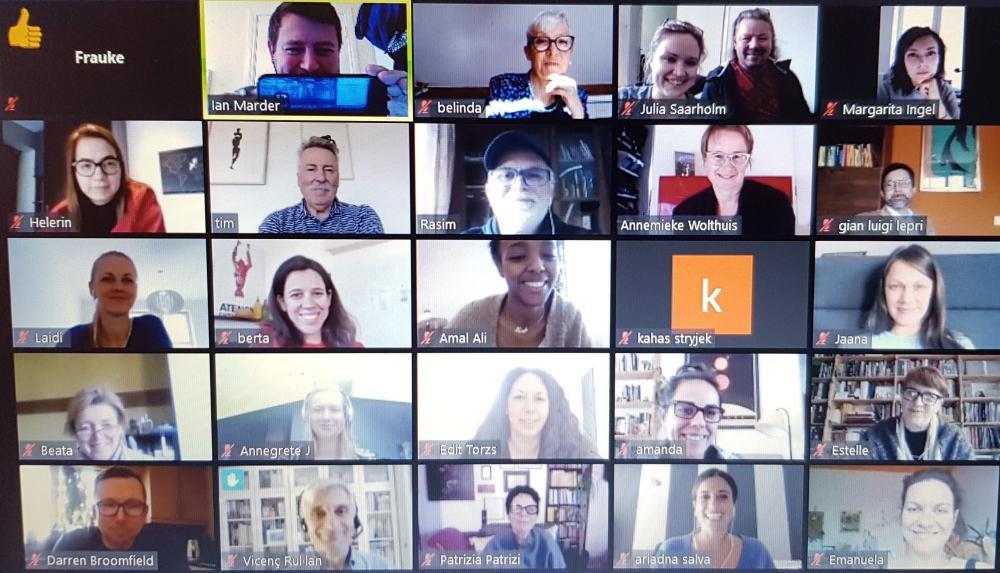

The group will meet online again next month (Monday May 4th, 11am UK, 12 noon Brussels, 13:00 Estonia) to update each other on their pilots and experiences. In the meantime, we ask that everyone continue to publish and share their experiences and experiments, so that we might learn from each other in this time of crisis and uncertainty. For example, you can find a guide to delivering online support circles in response to social distancing (written by Kay Pranis) here, and a guide to virtual community circles (aimed at school students and written by Laura Mooiman) here. The European Forum for Restorative Justice launched on open call for restorative practitioners and other experts from related fields to share their experiences about how they are responding to the extreme challenges that we are currently facing.