Integration not demonisation

A key restorative principle is the reintegration of both ex-offenders and those who are marginalised, which goes some way towards building a more cohesive society. The latter “does not advocate homogeneity of culture, but a pluralist society where members from different cultures foster a bond with the help of continuous social

interaction.” Various international instruments have outlined the importance of creating a safe environment for migrants where they can express their own traditions and deal with the trauma of being displaced.

Rundell, Sheety and Negrea have analysed how restorative processes enhance the autonomy of migrants, taking as an example an experience in a refugee camp in Europe. Their main assumption is the fact that restorative processes can diminish refugees’ trauma, by helping them to feel confident and be heard. This aim is achieved by restorative circles, during which specific restorative questions are addressed and people work together without relationships of subordination.

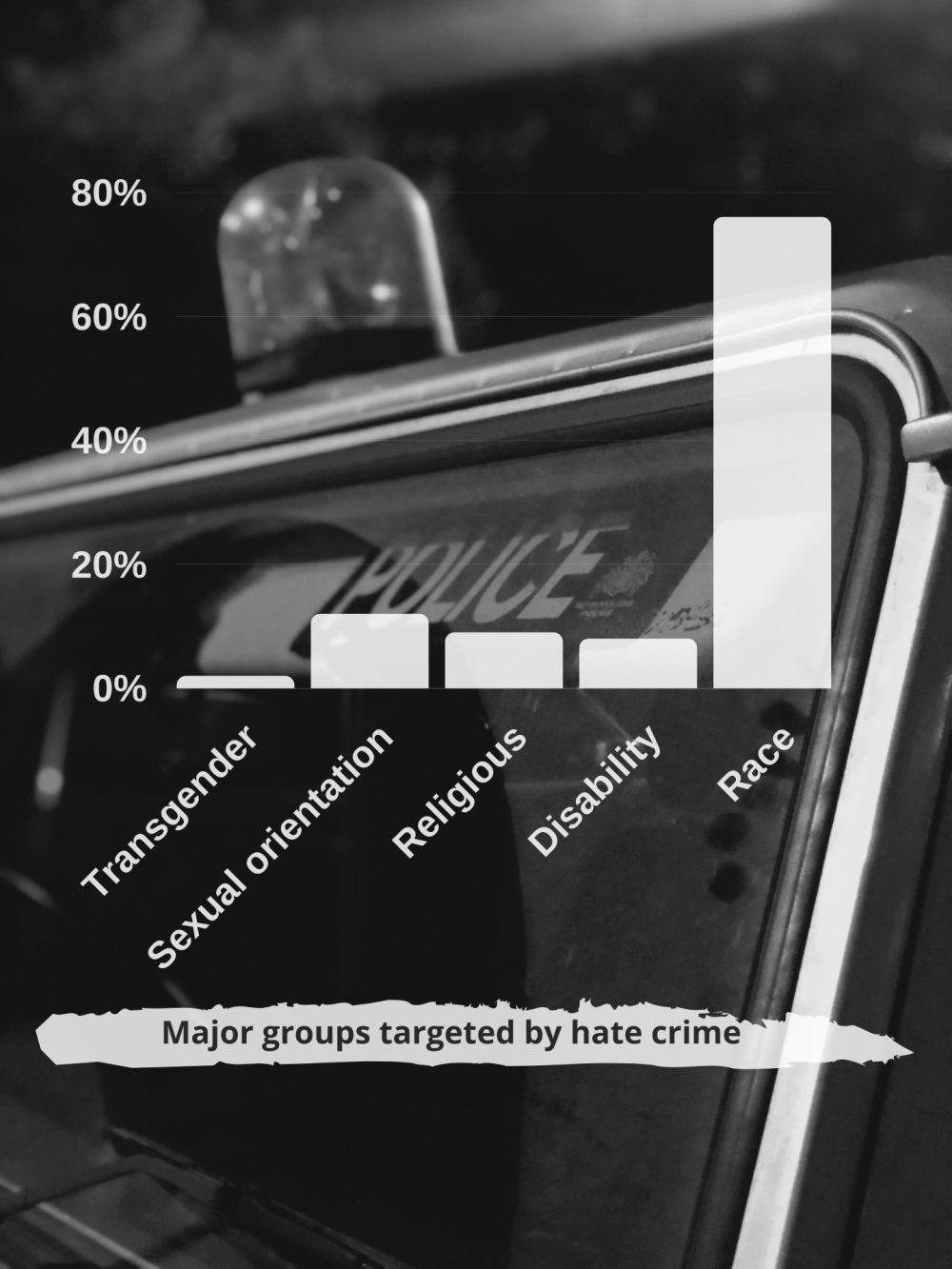

In August 2017, the British All Party Parliamentary Group on Social Integration published a report entitled “Integration, not demonisation.” They pointed to a marked increase in incidents of racist abuse directed at migrants and an unprecedented spike in racially or religiously aggravated hate crime in the months following the European referendum. They called for a major drive to integrate immigrants, warning that they increasingly lead “parallel lives” in Britain.

Chuka Umunna, former MP and then-Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Social Integration, said in 2017:

“The demonisation of immigrants, exacerbated by the poisonous tone of the debate during the EU referendum campaign and after, shames us all and is a huge obstacle to creating a socially integrated nation. We must act now to safeguard our diverse communities from the peddlers of hatred and division while addressing valid concerns about the impact of immigration on public services, some of which can contribute to local tensions.”