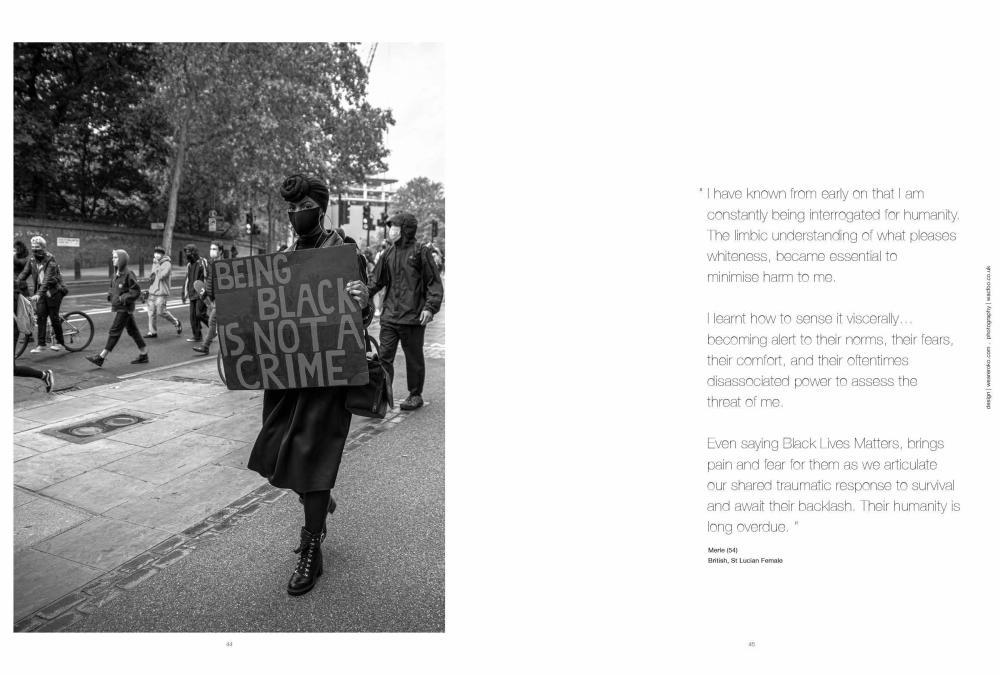

Demonstrating racism

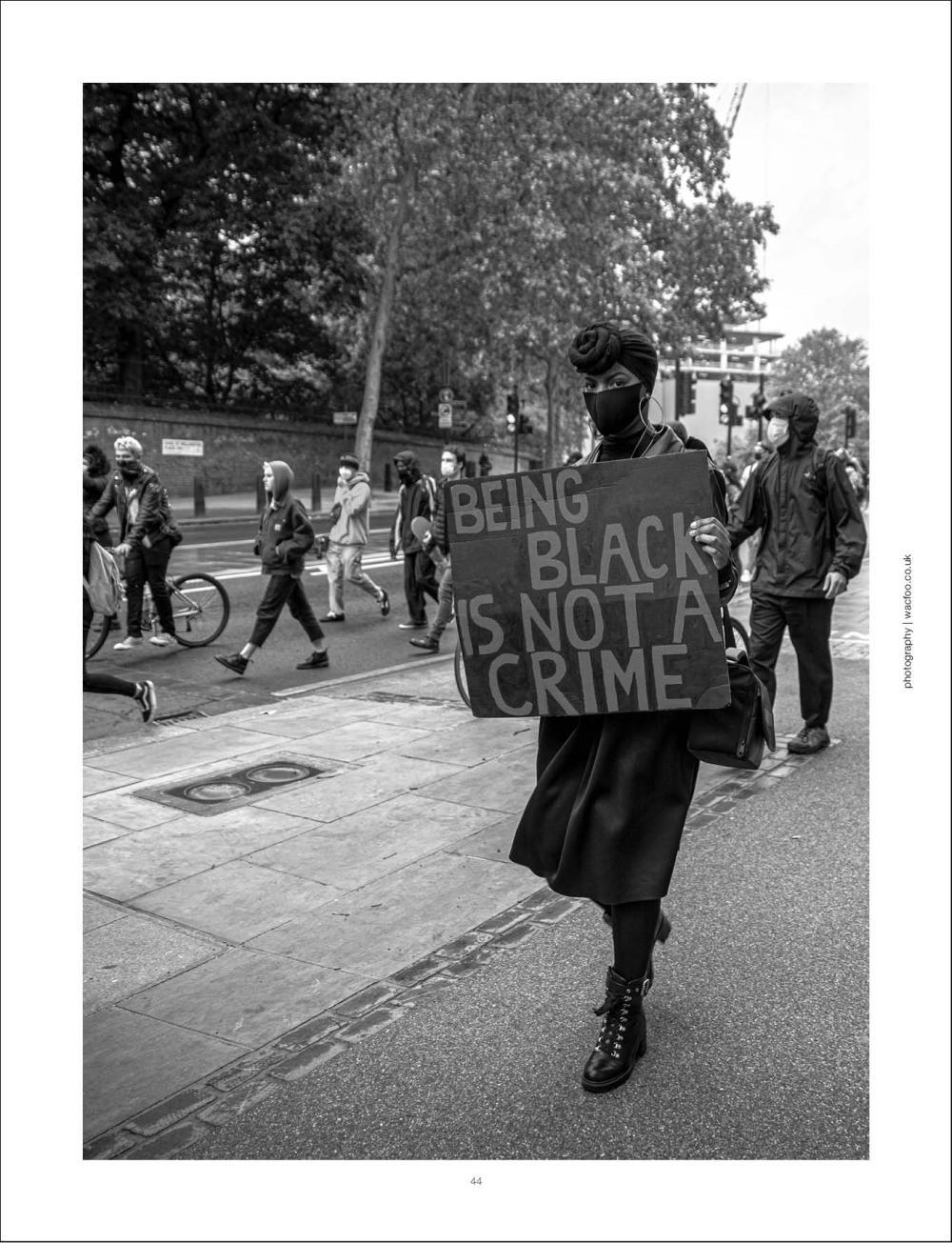

On May 25th 2020 in the US city of Minneapolis a 46 year old unarmed black man died following the excessive use of police force. In the hours that followed footage of George Floyd, lying handcuffed on the ground with a police officer’s knee pressed into his neck for over eight minutes, went viral. The sense of anger, pain and injustice at yet another such incident motivated people all around the world to take to the streets in protest. In the UK, and defying the Covid-19 related recommendations to avoid large gatherings, people marched in solidarity with their US cousins and also in recognition of their own challenges around racial injustice.

Across the country a number of photographers, professional and amateur, attended these protests, capturing images of the crowds. The marches were an outpouring from people who felt that the hurt and injustices that they had faced as individuals and as a group had long been ignored. But the crowds, diverse in ethnicity and age, showed that a wide cross-section of society had been motivated to mark their opposition to racism. The images that emerged are captivating, and show how the photographers were clearly inspired by the evolution of the energy in the crowds. First there was hurt and pain as protesters cried out angrily and struggled to repress tears. The collective sharing seemed to be greatly cathartic and protesters appeared to recognise their own frustrations reflected back at them by other demonstrators. A sense of community, safety and strength in numbers, developed and a feeling of hope became palpable. At times large groups of strangers danced joyfully together in the street. Pictures from a number of different photographers have been used as the basis of a book, Black Britain Demonstrated (BlkBritDem), that it is hoped will be published in the coming months.

In making BlkBritDem we wanted to capture and the energy of the marches and re-present it in a way that would inspire, and maintain the momentum for change. Motivated by a strong belief that the protesters’ concerns should not be forgotten, in our small creative team, we were all keen to draw on the skills from our ‘day jobs’ to produce a piece that would have strong social capital. Creative director Tatiana Okorie and producer Rochelle Ackie not only bring strong artistic skills and technical knowledge, but also draw on personal and professional experiences around racial integration, women’s rights and intersectionality. I have been able to draw on my experiences as a researcher with an interest in restorative justice when working on previous creative work, such as educational packages for schools (film and lesson plans) on violent extremism.

In BlkBritDem we acknowledge the pain but recognise that it is only one part of a much more complex story. Our work revolves around three central aims. Uniquely presenting the black British experience:

- Re-imaging. Recognising the contributions of black people to British society and re-framing what it means to be black and British;

- Re-imagining. Capturing social history to reduce misrepresentation;

- Re-documenting the future. Readers will be engaging by the bold images and, hopefully, drawn into a conversation about human rights and dignity.

We give a platform to protesters’ voices by highlighting their concerns and strength of feeling. Quotes gathered during and after the marches cement the book in the lived experience of citizens and are presented alongside over 200 reportage photographs. Conveying the spirit and energy of the crowds, BlkBritDem has been divided into chapters representing anger, empowerment and hope. As well as portraying these events, in BlkBritDem we reflect upon the wider context of the experiences of black people in Britain. It was considered important, in a book focused on a collective experience, to not lose sight of individual stories. The anger chapter, for example, features a section on ‘everyday racism,’ for which experiences of casual racism were gathered. One woman shared how she was told, supposedly as a compliment, ‘you’re quite pretty for a black girl.’ Consideration is also given to factors that have contributed to black people, and those from other minority backgrounds, still feeling displaced and disadvantaged in British society. The invisibility of black people in British history is one such example. We attempted to counterbalance this by, for example, highlighting the contribution of people from African and the Caribbean to British military efforts, tens of thousands of whom died fighting in the two World Wars.

The rallies were also places of empowerment and this is reflected in the second chapter. The photographs have a lighter, but still markedly determined tone. Throughout the chapter members of the African diaspora are highlighted for their positive contributions at global and local community levels. Mirroring the courage and strength that was generated when the protesters came together en masse, the chapter ends with a list of over a thousand inspiring people, past and present. Achievements in science, literature, philosophy and the arts are all featured.

The visual and emotional journey of BlkBritDem concludes where we would like the conversation to begin, on a powerful note of ‘hope’. The images in the final chapter are more joyful and even celebratory, portraying the resilience and strength of spirit during the marches. ‘Everyday heroes’ vignettes have been gathered for which people have described a friend or relative who has inspired and encouraged them. Later in the chapter the light is shone on some of the many contributions of black people to British culture. The influence of Africa and the Caribbean on language, cuisine and music, to name but a few, are presented in a colourful infographic. The quotes in this chapter make reference to the power of cross cultural solidarity and the importance of honouring each other’s humanity.

The effects of the colonial past are experienced as a present day reality by too many people in our society. The protests make clear that past hurt does not easily fall away with the passage of time. Particularly when a group feels wronged, an attack on one member can ripple out and be felt by many. Needs around giving voice to pain and suffering and expressing and being heard are essential for people who feel wronged as an individuals or at the group level. Restorative justice processes, such as circles, could have an important role in giving voice to such hurt. In exercising their individual responsibility each protester contributed to something that became much greater than the sum of its parts. Community level responses are important but we should remember that we are all part of the community and not underestimate the power of our actions, or lack thereof. Through documenting, giving voice to and acknowledging these stories, BlkBritDem aims to become a part of the community striving for racial justice, ‘I hear you. I see you. I walked with you.’ In doing so the book reflects the protesters’ main message, one of solidarity and hope.

Monique Anderson

Researcher and PhD candidate, Leuven Institute of Criminology, KU Leuven, monique.anderson@kuleuven.be

Photography: wacfoo.co.uk | Design: weareroko.com