This has left local organisations and networks that provide and promote restorative practices to carry the load individually and independently. How are they accomplishing this during the pandemic?

Groups with track records such as CCI have had some notable success in adjusting their programmes effectively during the Covid-19 crisis. Working to secure the release-under-supervision of more than 300 prisoners awaiting trial at Rikers Island, they collaborated with the NYC Mayor’s office and other support agencies to devise a system for supervision during social distancing, providing both necessities for newly released prisoners lacking resources and ’phones to ensure that they could maintain supervisory contact during the pandemic.

Another New York City agency, exalt, works with adjudicated teens in court to avoid indictment and incarceration, and provides support programmes and internships. With state courts in New York having suspended all non-essential functions, the organisation is working with prosecutors to see if there are openings to dismiss charges against youth who participate in exalt programmes, through which they learn life skills, pursue academic achievement, set goals and participate in training and paid professional internships — adapted to include online peacebuilding circles and virtual internships during social distancing.

Working with at risk youth outside schools, Eric Butler has adapted circles to the virtual format. He has facilitated remote training in circle keeping and online talking circles with youth from California to Alabama and acknowledges the difficulties. They are lacking the energy that is palpable in a room when people come together and they cannot be sustained as long as in-person circles. Yet Eric has found advantages to this online format as adolescents step into their leadership in technological know-how, recognise that they have something to teach as well as to learn and begin to focus on problems at home, allowing richer conversations about root causes, community needs, and values held in common. They discover that the same social media that has been used to cause or escalate conflict can be used to de-escalate or solve conflicts and they can start to shift their electronic communications.

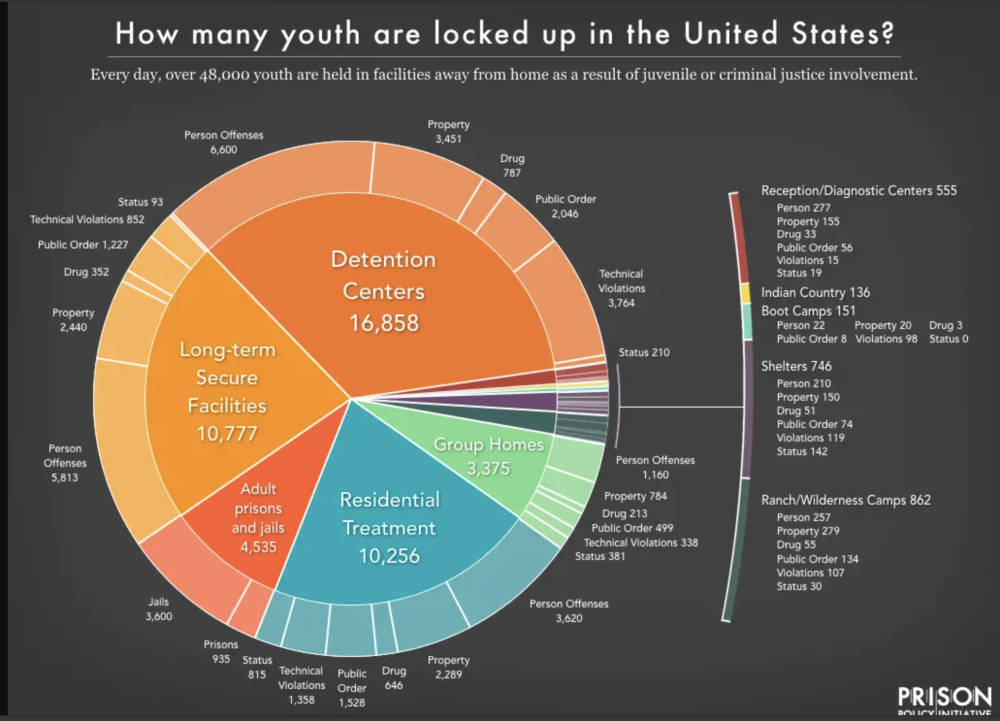

These inspired diverse efforts are a drop in the bucket given the overall numbers; according to the Prison Policy Initative, on any given day as a result of adjudication upwards of 48,000 juveniles are detained in a variety of settings, from adult prisons to halfway houses, across the USA.

The Sentencing Project has found that in total there are over two million people in prisons and jails throughout the country. Without a robust nationwide RJ effort in place, making headway to reduce these numbers during the Covid-19 crisis is in the hands of local governing agencies, which are focused on salvaging their economies before elected officials can bring attention to collaborating with restorative justice providers on reforms that, in the final analysis, can be controversial among some of their constituents.

Figure: Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie 2019